The lessons learned from delivery of medical supplies between hospitals in the UK and from the UK’s Civil Aviation Authority Sandbox research with detect and avoid (DAA) systems were the subject of a webinar organised by the European Network of U-space Demonstrators on 11 November, involving Bryce Allcorn, Principal Consultant & Head of Global Ops with Consortiq; Duncan Walker, CEO of Skyports and Moderator Munish Khurana, Head of Business Development at Eurocontrol.

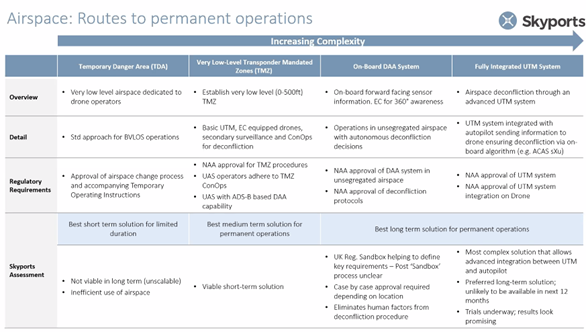

For Duncan Walker, the groundwork has been laid to a roadmap which could see permanent commercial operations in unsegregated airspace with 12 to eighteen months. “It’s complicated, but we see a clear route to get there,” he said.

So what are the lessons, the challenges and the milestones required?

According to Duncan Walker the first step will mean moving drone operations from temporary danger areas (TDAs), where the drone operator has temporary but complete control of the airspace, to transponder mandated zones (TMDs), and then unsegregated airspace operations (see main picture). States such as Dubai have already built TMD airspace areas where the airspace manager has a very high degree of control, where there is a high degree of compliance by airspace users and where there are significant ramifications if users do not comply. “But this is difficult and expensive to scale because you need a lot of ground-based technology.” The next evolutionary leap is to integrate detect-and-avoid equipped drones (being tested in the UK currently within the CAAs’ sandbox programme) into unsegregated airspace. There are technical issues to this – including making DAA systems small and light enough to be integrated within current drone platforms and to make them effective in flying against moving backgrounds, like the sea. But these are challenges that be overcome and need to be part of a long term solution which can be deployed to detect flocks of birds, for example.

Understanding the needs of all airspace users is challenge number two. Skyports has been part of a trial to ferry medical supplies between mainland Scotland and the Isle of Mull, 17km away, in a TDA beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) trial and one of the wildlife hazards faced was the challenge of eagles. But other airspace users also provided pushback: emergency responder helicopter pilots did want a drone alert system that added to their already heavy workload, so that meant looking at range of solutions. “It will need significant engagements from European and local regulators and – possibly a bigger challenge – significant engagement from general aviation community, emergency services and the military.”

Understanding the operational limits of drones is also a challenge not always fully appreciated. Very few drones have performance specification sheets that closely match operational performance. “We found that the wind at 100m in the air is very different from the wind on the ground; our 17km route would normally take around 18 minutes to complete. The fastest we did it was 12 minutes and the slowest 24 minutes. This becomes a particular challenge if you are pushing a drone to its limit so we had to repeatedly test the boundaries of the drones relative to the specs.”

It is also important to close the gap between perceived regulatory risks and real-life drone operational risks. The current Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) is time consuming for both regulators and operators and may not reflect actual risk profiles. In Scotland Skyports delivery operation had to avoid flying over people – but that meant doing a very aggressive climb up to 120m with a full payload, which from a vehicle performance viewpoint might entail a higher risk than flying the drone over a sparsely populated area such as an industrial estate.

Consortiq’s Bryce Allcorn agreed. “The safety case needs to be more analytical. The current risk scoring process is vague, subjective and somewhat arbitrary.” Consortiq has been supporting BVLOS operations around the world and has seen a wide variety of different of perceptions and rules. For example, there are major differences in interpreting visual line of sight (VLOS) limits – in the USA a drone can be just a tiny dot in the sky and still be flying within VLOS limits but this was less likely in Europe. In the USA, the challenge of public perception was manifested by angry neighbours concerned with privacy issues and threats to shoot down the drone; in India, trials of medical products were met by public concerns about money being spent on experimental delivery technologies rather than doctors and nurses.

And when delivering cargoes of dangerous goods, drone operators have to ensure their teams are trained in manage hazardous goods transport operations and the drone cargo holds have the right specifications to meet the challenge. “All current regulations on flying dangerous goods apply to manned aircraft,” he said.