The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has published its proposed methods on how to certify hybrid or electric air taxis. David Gleave, safety editor with Unmanned Publications, assesses the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed regulations.

Many in the safety community were hopeful that the introduction of standards for vertical take off (VTOL) air taxis would be the opportunity for overhauling the disjointed regulatory system currently endured by the fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft world. Each hazard would be addressed through an integrated set of requirements so that each organization knew the role that it had to play. Unfortunately, the vehicle design standards do not appear to have grasped that long-awaited opportunity by cross-referencing the other design and operational standards, such as vertiport design and UTM service provision, to give a complete understanding of how each hazard will be managed in the future – though this may be part of a future integrated safety regulatory regime which has yet to be fully explained.

Will the future VTOL air taxi operations suffer from omission of regulations between the silos and poor verification of some of the published requirements?

Bird strikes are mentioned in the standards but not the mass of bird to be considered only a likely bird impact. If a 0.5 kg bird is considered as the design basis then will this mean that many cities with much heavier raptors will be out of bounds for operations? By not cross-referencing the responsibilities expected of each organization, will the flight operator assume that the vertiport operator has kept the birds away but the vertiport operator assumes that bird strikes can be managed without affecting the safety of the flight? While the airport operator has to ensure that the fencing and other control measures are adequate to prevent such an encounter, will this be included in the vertiport standards?

The bird strike requirements for aircraft cover the critical areas of windshields and propulsion units as well as the leading edges of wings and tails but which areas must be considered for the VTOL machines? Are encounters with flocks of birds to be considered?

What about protection from insects as their nests in areas such as pitot tubes have led to false airspeed readings in the past?

The injury criteria for impact are those used in current aircraft design. This allows head impacts which can cause a loss of consciousness for some minutes. This obviously precludes the person evacuating the aircraft in a short period of time. Has the post-crash fire protection of the cabin taken this delayed evacuation time into account?

The spread of fire amongst VTOL aircraft made of modern materials can leave little remaining wreckage as anyone that has seen pictures of V-22 Osprey accidents can confirm. How will fire-fighting media address modern energy cells such as lithium batteries when the equipment is optimised for standard aviation petrochemical fuel types? Are there any special protection requirements for the fire-fighters to wear when tackling a blaze of modern materials? There appears to be no requirement for the manufacturers to provide information to vertiport, heliport and aerodrome operators.

The fitting of recorders is a welcome addition to airframes. With the new low mass combined data, voice and video recorders being installed in helicopters, it would seem that these would be the way forward. Strangely, for a device meant to help investigators determine what went wrong, the wording of the power requirements does cause some concern. The use of the phrase “most reliable power source” might indicate some manufacturers progressing by powering the recorders from one of the main batteries. If this had to be shut down, for example, with an overheat, then recording would be lost. If the flight were to operate in a state of low remaining power, or have an emergency, then the wording might imply that the recording devices could be left unpowered. These might appear to be the very situations when the recorders might prove most useful.

Modern technology is recognised in the ability to stream data rather than record on-board. Whilst linking to future satellite constellations can be seen, it may be cheaper and require less power to link to Earth via cellular telephone networks. This might save a significant element of the recorder’s mass and installed volume, in that the heaviest and bulkiest parts are associated with the crashworthiness protection of the memory media. Questions will be raised, as they have been in the fixed-wing world, about how the data are to be transmitted/received when the aircraft are in unusual attitudes just prior to an accident.

Once again, the standard certification tables mentioning one catastrophic failure per billion flight hours for each failure condition are mentioned, together with other values for the less serious failures. The theory that there might be one hundred catastrophic failure conditions needs to be verified. The lesser failure conditions mentioned in the table (minor, major and hazardous) are meant to combine with flight crew error probabilities to provide an acceptable accident rate. There continues to be a big debate about the use of these categories and the certification of the Boeing 737 MAX. Will there be a discontinuity between the expected standard of pilot knowledge, training and experience anticipated by the designers in selection of these categories and the actual performance of pilots?

While the tougher criteria apply to the enhanced category which allows for flight over built up areas, how has the third party risk been considered by a regulatory regime only used to protecting the occupants of an aircraft? Some countries have limits on third party individual risk exposure which may restrict the location of vertiports. Countries that manage risk in an even more advanced manner have limits on third-party group exposure as well as individual exposure. There can be a failure to link up the regulation of flight operations with the exposure on the ground.

| EASA’s proposed air taxi certification requirementsThis proposal is the latest milestone in EASA’s roadmap to enable safe VTOL (Vertical Take-Off and Landing) operations and new air mobility in Europe. The first building block published in July 2019 contained the certification framework for manufacturers to start developing innovative air taxi vehicles (Special Condition VTOL). The second block proposed certification requirements for electric and/or hybrid propulsion systems and is currently subject to a public consultation until June 19, 2020.

According to EASA: “Now that the industry is moving from prototypes into more mature designs, guidance on how to comply with the certification requirements is needed. The third block published today therefore proposes means of compliance for key certification requirements such as the structural design envelope, flight load conditions, crashworthiness, capability after bird impact, design of fly-by-wire systems, safety assessment process, lightning protection and minimum handling qualities rating. These subjects were identified and discussed with industry members and representatives from other aviation authorities worldwide. The requirements and guidance cater for a wide variety of flying vehicle architectures and enable innovative designs. The scope for the guidance remains “person-carrying small VTOL aircraft with 3 or more lift/thrust units used to generate powered lift and control”. “Some preliminary information – presented at the last EASA Rotorcraft & VTOL Symposium in December 2019 – is available online. The Agency will continue working with industry to enable them to develop new forms of mobility. This will be followed by additional guidance to extend progressively towards new technologies as they emerge. “The next package of guidance material will be presented during the 2020 EASA Rotorcraft and VTOL Symposium scheduled November 10 – 12, 2020 as part of the new Rotorcraft event EUROPEAN ROTORS.” For more information https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/Proposed%20MOC%20SC%20VTOL%20Issue%201.pdf |

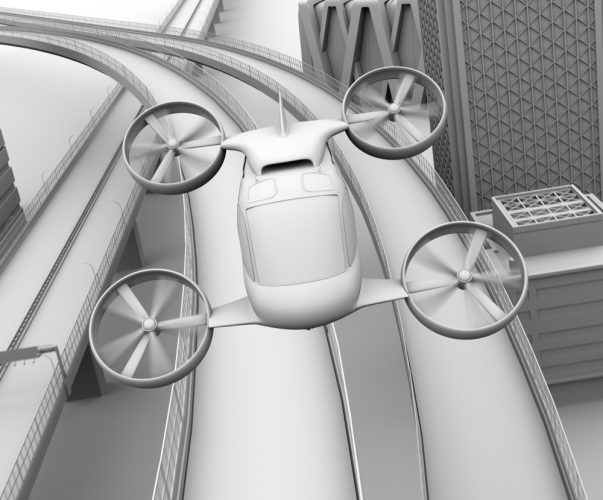

(Image: Shutterstock)