By Scott “Gripper” Brenton, NUAIR Chief of Safety

This post Drone Flight Safety Management appeared first on the NUAIR website (https://nuair.org/2019/11/04/drone-flight-safety-management/) and has been republished with the kind permission of NUAIR.

Safety Management is a concept that means different things to different people across a wide variety of organizations. A lot has been written about safety in the world of aviation where, in fact, the culture and standards have matured probably more than in any other industry. These solid foundations have matured over decades and have adapted to ever-increasing technologies and use-cases. Most recently, the advent of unmanned aviation has challenged those in the safety business with a host of brand new concepts and problems; but for those of us managing safety at an FAA-Designated UAS Test Site, these challenges become particularly unique.

Anyone familiar with industry standards knows that they vary quite a bit. Standards bodies such as ASTM, ISO and others (including the FAA) often overlap with policies and level of effort. Safety standards are no different, and often suffer from this effect as well. Here at Northeast UAS Airspace Integration Research (NUAIR), we have adopted some key industry standards as our bedrock. We have a well-documented safety program in our general operating procedures manual that is reviewed and updated annually. Within this program we have established policies that define our Safety Management System (SMS) from end to end.

“We believe that safety is a core value along with a competitive advantage.”

The SMS is integrated into every operational event, beginning with the planning stages, and continuing through deployment, ground operations, flight operations, post-flight analysis and maintenance, and ending with a thorough debrief among the relevant team members. That level of risk control is truly the heart of any good SMS. As Chief of Safety, I report directly to the Chief Executive Officer, bypassing any bureaucracy or communication barrier, which has proved very successful in ensuring that our SMS remains relevant, adaptive, and effective in controlling risk.

Risk Management (RM) is fundamental, but the methods of RM are wide and varied throughout the industry as well. At NUAIR, we begin the RM process by first meeting with potential clients, having them provide us with their concepts and as much detail as possible about their equipment. This can be a challenge at a test site where clients range from industry giants like NASA or Boeing all the way down to the three-person startup company with an aircraft that is 100% proprietary.

The documentation received from these companies range from published Technical Orders which are highly detailed and hundreds of pages long, to self-prepared Microsoft Word documents that may only be paragraphs long. We expect every client to have a complete pilot’s operating manual and maintenance manual and expect their maintenance practices to be able to track all modifications (hardware and software) effectively. This may appear fundamentally obvious, but the levels of detail that we see are often quite diverse.

Documentation covers equipment primarily, but we then need to fully understand the proposed test flights themselves. Again, this varies widely across our domain of clients. A concept of operations (CONOPS) is key and needs to ensure we fully understand the objectives and parameters. Flight paths in four dimensions are generally depicted pictorially to allow simple visualizations. That is critical for the safety team to begin to identify the hazards we will address during the review process as we assess risks. The industry leaders who are familiar with flight test management will often then produce highly detailed test cards, with all test points and parameters clearly defined and organized for a pilot to execute in real-time. The less-experienced may simply trace the ground-track on top of a google-earth image for us

As the Chief of Safety, if I don’t get the level of details that I need in the planning stage, I don’t simply say “no” and reject a less-experienced client. Instead, I work with the client to help them develop and refine their internal programs to achieve industry levels of best-practices which helps us move forward with testing and sets them up for success for future visits.

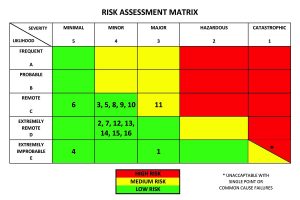

Armed with this plan, we now roll up our sleeves and jump into the analysis of RM. We utilize a qualitative RM process where we identify all hazards and the associated severity and likelihood of each. From this table we then score the level of severity from an un-mitigated standpoint first and then develop strategies for each identified hazard in order to mitigate those risks down to the lowest practical level. Those mitigation schemes involve anything from restricting altitudes, air speeds, flight paths, RF spectrum values, buffer-zones, weather tolerances, communication game plans (radio, link, etc.), and similar aspects. Additionally, we establish higher levels of protocols for more complex operations such as multiple, simultaneous unmanned or mixed manned/unmanned operations for instance.

Flight Plan Example (AirMap App)

NUAIR utilizes a Risk Matrix defined by Mil STD – 882, but we have worked with clients such as NASA who may expect other types of standards and processes. In general, this is very easily accommodated. The highest level of mitigated risk will define the overall risk score for the test and will require a varying level of approval authority from myself, for low risk operations, all the way up to the test site director for high risk situations.

Lastly, we conduct an Independent Safety Review Board (ISRB) with impartial voting members that have expertise in the field. This process brings the clients, NUAIR staff, and a panel of third-party members together to finalize the game plan for the upcoming event. We then monitor and assist with the actual flight test at our various facilities with a specific level of management that is scalable to the size and complexity of the event. Regardless of the scope, we always have a certified Mission Crew Commander (MCC) who has the “hammer” in terms of conducting a Flight-Readiness Review (FRR) and pulling the plug at any time in the interest of safety. In the event that an incident occurs, the MCC has a quick-reaction checklist to handle the incident response in the field, and the safety department quickly reacts to begin any internal investigation. I personally manage investigations and produce the final reports that are published both internally and externally with any recommendations or policy changes.

IR’s iterative process has worked well at the New York UAS Test Site and keeps the team members aware and engaged with safety as a concept in everything we do. As a test site, we accept an increased level of risk that is occasionally higher than independent clients would be able to support on their own. A great example has been our recent support of two different clients who conducted ASTM certification tests of their parachute recovery systems (Indemnis & Flytrex/Drone Rescue Systems). Each of these test sequences involved 45 separate flights where the objective was to essentially force the aircraft to seriously malfunction in various but controlled flight parameters, then examine the success or failure of the parachute systems to preserve the aircraft as it crashes to the ground! If that isn’t unique for a Safety Management System, I don’t know what is.