By Philip Butterworth-Hayes

The slow rate of U-space adoption in Europe is starting to take its toll on the European drone and wider advanced air mobility industries. There are growing concerns about the mounting failures of European drone and eVTOL companies who cannot scale their business plans and who are who being forced into bankruptcy or take-over by north American and Asian competitors – essentially transferring European technical know-how outside the continent. There is also a concern by some that over-regulation might at some stage encourage operators to circumnavigate the rules and adopt their own, less safe, practices.

At the latest European Network of U-space Stakeholders meeting, which took place on 24-25 June 2025 in Hamburg, the consequences of slow progress and potential remedies were scrutinised in detail. The event was organised by the Support Cell (comprising the European Commission/DG MOVE, EUROCONTROL, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, the SESAR Joint Undertaking and the European Defence Agency).

Over the past few years these network meetings have become very good at articulating problems around U-space adoption and this meeting was no exception. There are currently at least five main areas of concern.

Regulators have limited resources and they often must choose between working to approve beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) flight requests or implement U-space. They cannot do both at the same time. There is still a lack of agreement between Member States on how data should be shared between the common information service provider (CISP) and the U-space service provider (USSP). EUROCAE has a working group looking at this, but it is taking time to reach a consensus. Each stakeholder group in a U-space ecosystem has a different interpretation of how U-space should work: air navigation service providers (ANSPs), drone operators, non-aviation stakeholders – such as emergency service personnel and citizens – all have very different priorities.

There has of course been some progress (see The U-space certification scorecard).

| The U-space certification scorecard

Today, in the European Union, there are:

|

For many at the event, the two key issues were over-regulation and money.

Certificated USSPs speaking at the event said it generally took around two years to be certified from start to finish, which should come down once both sides become more familiar with the process. To become a certified CISP takes 10 months to a year; for companies like D-Flight, which are both USSPs and CISPs the timescale should be lower as core information is common to both. D-Flight also recommended having a single, large customer (which in D-Flight’s case was Amazon), which gave the regulator a much clearer idea about how the top-down and bottom-up regulatory procedures could meet in the middle.

And money was seen as another major sticking point.

The USA does venture capitalism very well but in Europe the financial resources needed to take a U-space company from start-up to successful commercialisation is complex. There is often interest from private venture companies in the early-stage investment (series A and series B shares) in exchange for equity in the company if they see a clear vision, differentiation, and a business model which evolves with market changes. Once the operation starts to scale up, public sector investors, like the European Investment Bank (EIB) who specialise in debt finance, can become more interested (typically in B and C series shares) because they can start to see real results and the risk levels are lower. Briefly put, in series A you need to sell a vision, in series B, you need to show results.

The problem is that in Europe, drone and U-space start-ups are often strong in technology and operations but weak in administration, finance and legal affairs – to be successful, a start-up has to tick all these boxes. And delays as a result of regulatory complexities make this financial route to market vulnerable.

So what is the remedy?

Ideally, said many of the meeting attendees, stronger support from government and EU organisations. There could be several ways this can happen: making it easier for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) to have access to government procurement contracts; political support for some kind of protection measures; increasing opportunities for collaboration with larger EU companies who are already deeply integrated into the global drone economy.

Another possibility – which is core to the EU drone strategy – is to bring the military and civil sides more closely together. For example, the European Commission (DG Move) has developed a policy for extending military test site facilities to civil operators, but this would also require military and civil regulators to start aligning some of their rules and procedures.

It is now clearer than ever that Europe has developed the technical and operational capabilities to implement U-space safely and efficiently. Hamburg hosts the BLU-Space consortium[1] , which brings together a range of local authority and industry groups to develop a non-certified U-space eco-system in which the port authority, emergency services and others safely operate a wide range of drone missions in a complex low level airspace. The key phrase here is “non-certified”. As all BLU-Space stakeholders re-iterated, if this system could be approved at federal level then the benefits it is currently bringing to the port and city could be exported throughout Germany.

[1] BLU-Space consists of a multidisciplinary consortium of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, Deutsche Flugsicherung GmbH (DFS), HHLA Sky Hamburg, Hamburg Port Authority AöR and Karl Koerschulte GmbH. The consortium leader is Hamburg Aviation e.V. The German Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport is funding BLU-Space with a total of EUR 2.36 million as part of the mFUND innovation initiative.

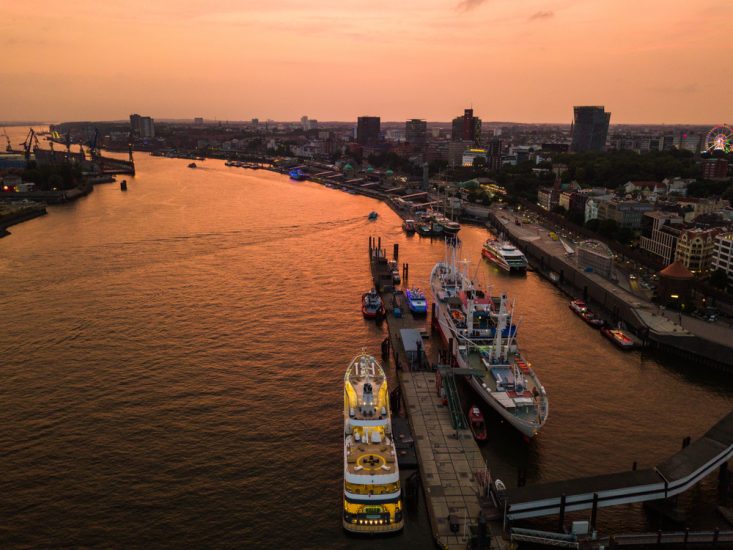

(Image: Shutterstock – sunset over the river Elbe in Hamburg)